The Appareil Respiratoire Tissot Mle.1916 and Appareil Respiratoire Tissot Mle.1917, also known as the French Tissot Mask was the first gas mask to incorporate the "Tissot Principle".

Early Development

Dr. Jules Tissot (February 17, 1870 - June 17, 1950) was a French Biologist who had experience developing spirometer equipment for the medical field in 1904 as well as being the inventor of an oxygen breathing apparatus designed for mine rescue in 1907. These devices were recovered at the end of April 1915 to be sent to the French army. Although they were used seldom, the only 250 copies existing were all used. On April 22nd, 1915, after the appearance of poison gas, Dr. Tissot initiated research on making a new apparatus for protection against gases.

The prototype was sent to the Commission and the various members, which organized and conducted a test at Lebeau Laboratory on January 8, 1916, to evaluate the capabilities of the apparatus. The test subject entered the test chamber filled with benzyl bromide and phosgene gases and was observed as gas was gradually added to the atmosphere. After 20 minutes, feeling a slight tingling in the eyes, the experimenter came out of the room and the test was concluded.

A second test at Satory was conducted outdoors on January 14th, where Dr. Tissot was invited. The purpose of this test was to have the test subject traverse through clouds of phosgene, chlorine, and arsine smoke gases, beginning 50 meters from the gas canisters. The older TN mask would be trialed along with Tissot's device and timed how long one could go without feeling the effects of chemical agents.

The Tissot apparatus was ruled as the superior mask upon completion of the testing, so the Commission, therefore, proposed to continue the development of the Tissot Apparatus, not to substitute for the other masks in service, but to replace the Draeger Rebreather and other oxygen breathing apparatus. These types of gear were used in high-concentration toxic environments since they are entirely self-contained.

Their main disadvantage is their period of use, which may not exceed half an hour. The Tissot Apparatus was, therefore, a real advantage, but these expectations needed further proof and additionally, to establish the duration of use with different types of gases and concentrations. After extensive tests, it was found out in light gas concentrations, the device could work up to 50 hours before being exhausted, and 30 hours in extreme conditions. It protected against all period chemical warfare gases, unlike some of the older masks.

The Committee decided to produce an initial 1,000 units to continue research in order to arrive at a production model. On April 29, 1916, testing was concluded. On this date, 450 Tissot masks had been manufactured and 50 were tested by a company that produced toxic gases. Unanimously, the Tissot apparatus was chosen and adopted. Delivery of the masks to the front lines started that same year in the month of July.

Facepiece Overview

The Tissot Principle

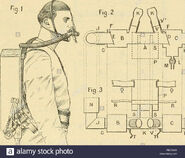

Dr. Tissot had sought to avoid fogging on the panes of glass by cooling the inside of the eye by a special system: each time the user inhaled, air arrived in the mask by two pipes around the eyepieces, so they were constantly exposed to fresh cold air, preventing condensation. Similar systems were already developed for commercial diving helmets, but Dr. Tissot's mask was the first air-purifying respirator to employ such principles.

Characteristics

The entire mask, including the head harness, was made of a black or grey 'cold-vulcanized' gum rubber. The glass eyepieces were attached to the mask with reverse-crimped metal rings, and an air inlet/outlet angletube system consisting of black varnished copper/brass tubing that housed the hose connector and the outlet valve.

As stated before, the clarity of vision was improved by the so-called Tissot tubes that deflected incoming air at the interior of the eyepieces to prevent fogging. The two tubes were made of rubber and connected from the bottom of the lenses to the pipe leading to the hose. Metal insert ferrules were inserted in the eyepiece tube connections to prevent the collapse of the rubber tubing.

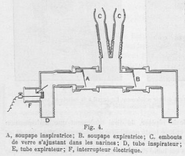

Exhaling was possible through a metal check valve that was located directly on the mask on a pipe angled upwards to prevent damage and blockage from debris. The intake tubes were soldered to this angled out assembly. Inside the mask, there was a folded wire spacer with rubber tube padding connected to the outlet port in the mask that prevented the collapse of the mask upon inhaling.

Improvements

At the end of 1916, a rubber flutter valve was added to the metal check valve assembly to prevent it from being clogged with debris or flooded with rain. Another development was made in late 1917 - The mask's gum-rubber facepiece tended to tear after a period of time, so some copies would thus be manufactured in the same way as the new ARS-17 Mask: the new facepiece came in 3 sizes and was constructed of rubberized fabric impregnated with boiled linseed oil that was twice as thick as the original gum-rubber faceblank.

Filter Unit(s)

Large (Grand) Model

In its first rendition, filtration was carried out by a rectangular, backpack-sized, gray-painted metal box containing two layers of filtering materials: two layers of steel wool saturated with a sodium hydroxide solution and a second layer consisting of wood chips soaked mixture of castor oil and sodium bicarbonate. The canister was carried on the back due to its large size via a harness of waxed cord, and on top of it, there were threads allowing the non-corrugated hose conjoining the filter to the facepiece to be connected. On the bottom, there was an air intake port with a rubber inhalation valve disk and a rubber plug to seal the canister when not in use.

An additional cartridge containing castor oil-impregnated sawdust was also added and connected under the canister at the inlet port. This smaller, auxiliary cartridge was threaded on the upper side and had a cap with a bayonet latch closure on the bottom to seal it. This smaller auxiliary filter allowed additional protection against arsine smokes, however it needed to be soaked for 5 minutes in water before use to moisten the chemicals impregnated in the sawdust to activate them, and thus the castor/sawdust filling was replaced with charcoal by August 1916.

Additionally, the castor oil-soaked wood chips of the main canister were replaced with charcoal as well between August 1916 and March 10, 1917, with the new canisters bearing a yellow star stamp while older canisters had a black star marking. The charcoal-filled 'Yellow Star' Large Model Canister began to appear on the battlefield at the end of June 1917, where it was soon learned the charcoal, which still needed moistening for arsine protection, would quickly dry up and was later replaced with an improved, pre-soaked charcoal mix in August 1917. The auxiliary smoke canisters containing the new charcoal were threaded on both ends and were painted entirely yellow to distinguish them from the earlier smoke canisters.

Between January and Summer of 1918, the sodium hydroxide + steel wool layers of the main canister were replaced with granulated soda lime to avoid severe chemical burns to the user when the solution is inadvertently inhaled into the facepiece from the steel wool. After this incident, to warn others of the dangerous old filters, the models containing the caustic soda/steel wool layers were marked with the inscription: "Don't forget to purge the canister after each use to prevent the flow of clothes-burning liquid". More than 100,000 units of the Grand Model Tissot were manufactured until the Armistice was declared in 1918.

Small (Petit) Model

Despite the superior protection, the Grand Model Tissot proved to be too ungainly, even for fixed position troops, so in November 1916, a smaller, lighter canister began development. On December 2, 1916, the canister was finalized as the 'Petit' Model and was comprised of seven layers of gauze impregnated with sodium hydroxide, with a layer of activated charcoal retained between two wire mesh screens packed by springs.

The protection offered by the mask and filter was excellent against most agents of the time until the introduction of German arsines in the Summer of 1917 - Diphenylchloroarsine could penetrate the gauze compresses and charcoal. It was determined that only cotton was capable of stopping these substances, so an additional auxiliary smoke canister, containing the hydrophilic cotton was developed and began issue in late 1918. Unlike its bigger, cylindrical brothers intended for the Grand Model Canisters, the Petit Model Smoke Canister was rectangular in shape with the same diameter of the main canister body and fixed in place with two cotton straps that were a part of the main canister's harness. This canister was marked with red paint on the top.

Much like the Grand Model Canisters, the Petit Models replaced the caustic soda + steel wool wet filter layer with granulated soda lime in the Summer of 1918. The new soda lime petit canisters were distinguished from the former caustic soda models by the lack of drain holes at their base and did not have a red band of paint. More than 590,000 units of the Petit Model Tissot were manufactured until the Armistice was declared in 1918.

Kit

The mask comes in a large rectangular wooden box painted 'horizon' blue with large black markings that read: "APPAREIL T" (Apparatus Tissot) to indicate what was contained within because it was not intended to be worn by a regular infantryman or soldier who needs to move from place to place constantly. It was considered a special sector apparatus that remained in place in a fixed position like its user (e.g. machine gunners, artillerymen, snipers, communications troops and combat engineers).

Success of the Petit Model and American Testing

In October 1918, it was decided to permanently replace the Grand Model Tissot with the Petit Model. By this date, all manufacturing had stopped due to the end of the war. During mid-1917, U.S. Army would procure several specimens of the Appareil Respiratoire Tissot Mle.1917 for testing and evaluation, with some even seeing service with the AEF with Medical and Signal Corps personnel.

Surviving Samples

Almost no examples of this mask survive. After almost 100 years since it was last manufactured, most Tissot masks have been lost to old age and due to the period materials not being as resilient to aging as today's synthetic rubbers. A Petit Model filter, angletube, chin rest, canister, and smoke canister without a facepiece were once in the possession of a collector named Boris Plotnikoff, but since his passing, it is currently unknown where the specimen is. A postwar Fernez-Tissot Industrial Mask is currently owned by Artist Viktor Ferrando. A Petit Model canister resides at the National World War I Museum in Kansas City, MO.